I’m working on a little longer piece on Emerson, again, but thought I’d just put up a collection of unrelated stuff in the interim.

Me On Teleread

I actually don’t remember if I said anything about this, but I should have if I didn’t. Dave Rothman over at teleread.org was kind enough to ask me to blog on his space. David says he wants the perspective of a humanist to complement all the techies. He was kind enough to not say “I want someone who doesn’t know jack about technology.” In any case, my first post over there went up last week. I may have forgotten it because I posted a version of it over here as well. Still, I’m very interested in the conjunction of technology and reading, so teleread is a good place for me to further that thinking.

On Being Healthy

The Canadian Council on Learning tells us that daily reading is better for you than fiber. Oh, wait…I think we just found out that fiber doesn’t do anything for you except forestall diarrhea. (For more on diarrhea, see my completely fascinating post on this topic.) In any case, I’m happy to discover the following.

Reading each day can keep the doctor away, says a report that concludes sifting through books, newspapers and the Internet — on any topic — is the best way to boost “health literacy” skills such as deciphering pill bottles and understanding medical diagnosis.

Daily reading, not education levels, has the “single strongest effect” on the ability to acquire and process health information, the Canadian Council on Learning said Wednesday.

=====

The learning council reported Canadians aged 16 to 65, who said they read daily, scored up to 38 per cent higher than the average on the health literacy analysis.

Daily readers over 65 years old scored as much as 52 per cent higher than the average for their age.

“Although it may not be a panacea, this report makes a compelling case that reading each day helps keep the doctor away,” said the report.

I think it’s wise to have a tad bit of skepticism about stats like this. I wonder if there are correlations between regular reading and social class, for instance, and if so is the relationship to health a function of reading or a more general issue of access to health care, material resources, and knowledge itself. Still, why look a gift horse in the mouth. At this rate I am going to live a good long time. Actually, I better stop blogging because it’s definitely cutting in to my reading time. (Who am I kidding, I just don’t watch TV anymore.)

Reading More or Reading Better

A blog over at Metafilter raises the typical objections to the notion that we’re in a reading crisis. So what if we’re reading less literature; we’re reading more than ever on the web, right?! On the other hand, they also point out that Americans ability to read at all seems to be declining, pointing to the following study at the National Center for Education Statistics:

On average, U.S. students scored lower than the OECD average (the mean of the 30 OECD countries) on the combined science literacy scale (489 vs. 500).

The average score for U.S. students was:

- higher than the average score in 22 education systems (5 OECD countries and 17 non-OECD education systems)

- lower than the average score in 22 education systems (16 OECD countries and 6 non-OECD education systems)

- not significantly different from the score in 12 education systems (8 OECD countries and 4 non-OECD education systems)

Ummm….One big problem, guys. Science and Math literacy is not the same thing as reading and writing literacy. And so I’m not quite sure what this has to do with whether people are reading literature any more or not. Though I’m sure Dana Gioia over at the NEA would be glad to claim that reading Moby Dick helps people with their algebra. Of course, it could be that reading skills have declined so far that the folks can’t even tell what science and math literacy really is.

Links:

A number of people have been kind enough to comment about the blog or link to my blog in various ways over the past several weeks. A few of them:

Free listens: A blog of reviews about audiobooks. What a great thing. I’ve said that I wish there were more sorting and evaluating of some of the free stuff on the web. Heresy of heresies, I don’t think massing blog stats necessarily tells me much about quality. I mean, videos of Brittany Spears’ pudenda are among the most popular on the web. Does that really tell us anything…about the quality of the video, I mean. Not about the state of America… or the state of Brittany Spears body parts. I haven’t had a chance yet to listen to the audiobooks to see if I agree with the judgments, but I’m glad someone is taking up the flag to do such a thing.

The Reading Experience: Daniel Green has me on his blogroll, and I’ve had The Reading Experience on mine from the beginning. I think Daniel is a little narrower in his literary judgments and tastes than am I, but I admire anyone immensely who has left academe and made it on his own. His blog is always thoughtful and often provocative.

There’s Just No Telling: “Monda” has commented on my blog before, and has a lovely sight devoted to reading and writing. From what I gather she is a teacher of creative writing, who all deserve to be sainted.

Brad’s Reader: Brad lists me as an interesting read. And I didn’t even have to pay him.

There are others that I’ve missed, and I’ve got to stop somewhere in any case. So if you’ve linked to me and I’ve missed you, let me know. I’ll keep you in mind next time I do this.

the nature of the comprehension we experience in reading versus listening. Second, while listening was taking place, there was more activation in the left hemisphere brain region

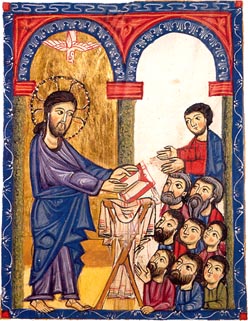

the nature of the comprehension we experience in reading versus listening. Second, while listening was taking place, there was more activation in the left hemisphere brain region  temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance,

temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance,  of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.

of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.