Some more about audiobooks today.

I still remember my shock and dismay a couple of years ago when I clicked on to the New York Times book page and found an advertisement of much a younger, more handsome and vaguely Mediterranean-looking young man who oozed sex appeal as he looked out at me from the screen with headphones on his ears.

“Why Read?” asked the caption.

Surely this was the demise of Western Civilization as we knew it, to say nothing of being a poor marketing strategy for a newspaper industry increasingly casting about in vain for new readers.

Nevertheless, it seems to me that audiobooks have developed a generally sexy and sophisticated cache for literary types that other shorthand ways to literature typically lack. As an English professor, I’ve been intrigued lately that a number of colleagues around and about have told me they listen to audiobooks to “keep up on their reading.” To some degree I’ve always imagined this as a slightly more sophisticated version of “I never read the book, but I watched the movie,” which has itself been about on a par with reading Sparknotes.

However, as I mentioned in yesterday’s post, another colleague recently took issue with my general despairing sense that the reading of literature, at least, is on the decline, no matter the degree to which students may be now reading interactively on the web. “Yes,” she said, “but what about audiobooks?” She went on to cite the growth in sales over the past few years as evidence that interest in literature may not be waning after all.

My immediate response is a little bit like that of Scott Esposito over at Conversational reading. In a post a couple of years ago Scott responded to an advocate of audiobooks with the following:

Sorry Jim, but when you listen to a book on your iPod, you are no more reading that book than you are reading a baseball game when you listened to Vin Scully do play-by-play for the Dodgers.

It gets worse:

[Quoting Jim] But audio books, once seen as a kind of oral CliffsNotes for reading lightweights, have seduced members of a literate but busy crowd by allowing them to read while doing something else.

Well, if you’re doing something else then you’re not really reading, now are you? Listen Jim, and all other audiobookphiles out there: If I can barely wrap my little mind around Vollmann while I’m holding the book right before my face and re-reading each sentence 5 times each, how in the hell am I going to understand it if some nitwit is reading it to me while I’m brewing a cappuchino on my at-home Krups unit?

It’s not reading. It’s pretending that you give a damn about books when you really care so little about them that you’ll try to process them at the same time you’re scraping Pookie’s dog craps up off the sidewalk.

I have to grin because Scott is usually so much more polite. Nevertheless, I cite Scott at length because viscerally, in the deepest reaches of my id, I am completely with him and he said it better than I could anyway.

However, it’s worth pausing over the question of audiobooks a little further. I don’t agree with one of Scott’s respondents over at if:book, who describes listening to audiobooks as a kind of reading. But it is an experience related to reading, and so it’s probably worth parsing what kind of experience audiobooks actually provide and how that experience fits in with our understanding of what reading really is.

As I’ve said a couple of times, I think we lose sight of distinctions by having only one word, “reading,” that covers a host of activities. I don’t buy the notion that listening can be understood as the same activity as reading, though the if:book blog rightly points out the significance of audiobooks to the visually impaired. Indeed, one of my own colleagues has a visual disability and relies on audiobooks and other audio versions of printed texts to do his work. Even beyond these understandable exceptions, however, Scott’s definition of reading above privileges a particular model of deep reading that, in actual fact, is relatively recent in book history.

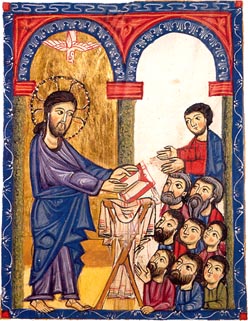

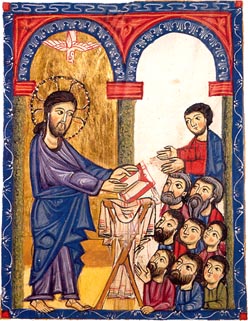

Indeed, going back to the beginnings of writing and reading, what we find is that very few people read books at all. Most people listened to books/scrolls/papyri being read. The temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance, it’s estimated that in even so bibliocentric a culture as that of the Jewish people only 5 to 15% of the population could read at all, and the reading that went on often did not occur in deep intensive reading like that which Scott and I imagine when we think about what reading really is. Instead, much of the experience of reading was through ritual occasions in which scriptures would be read aloud as a part of worship. This is why biblical writers persistently call on people to “Hear the Word.” This model of reading persists in Jewish and Christian worship today, even when large numbers of the religious population are thoroughly literate. See Issachar Ryback’s “In Shul” for an interesting image from the history of Judaism.

temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance, it’s estimated that in even so bibliocentric a culture as that of the Jewish people only 5 to 15% of the population could read at all, and the reading that went on often did not occur in deep intensive reading like that which Scott and I imagine when we think about what reading really is. Instead, much of the experience of reading was through ritual occasions in which scriptures would be read aloud as a part of worship. This is why biblical writers persistently call on people to “Hear the Word.” This model of reading persists in Jewish and Christian worship today, even when large numbers of the religious population are thoroughly literate. See Issachar Ryback’s “In Shul” for an interesting image from the history of Judaism.

Indeed, in the history of writing and reading, listening to reading is more the norm than not if we merely count passing centuries. It wasn’t until the aftermath of the Reformation that the model for receiving texts became predominantly focused on the individuals intense and silent engagement with the written word of the book. In this sense, we might say that the Hebrews of antiquity weren’t bibliocentric so much as logocentric—word-centered but not necessarily book-centered.

Along these lines, the model of intense engagement—what scholars of book history call “intensive reading”—is only one historical model of how reading should occur. Many scholars in the early modern period used “book wheels” in order to have several books open in front  of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.

of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.

But to recognize this is not exactly the same thing as saying “so what” to the slow ascendancy of audiobooks, and the sense that books, if they are to be read at all, will be read as part of a great multi-tasking universe that we now must live in. Instead, I think we need to ask what good things have been gained by the forms of intensive reading that Scott and I and others in the cult of book lovers have come to affirm as the highest form of reading. What is lost or missing if a person or a culture becomes incapable of participating in this kind of reading.

By the same token, we should ask what kinds of things are gained by audiobooks as a form of experience, even if I don’t want to call it a form of reading. I’ve spent some time recently browsing around Librivox.org, which I’ll probably blog about more extensively in a future post. It’s fair to say that a lot of it turns absolutely wonderful literature into mush, the equivalent of listening to your eight-year-old niece play Beethoven on the violin. On the other hand, it’s fair to say that some few of the readers on that service bring poetry alive for me in a way quite different than absorption in silence with the printed page. As I suggested the other day, I found Justin Brett’s renditions of Jabberwocky and Dover Beach, poems I mostly skim over when finding them in a book or on the web, absolutely thrilling, and I wanted to listen to everything I could possibly find that he had read.

This raises a host of interesting questions for a later day. What is “literature.” Is it somehow the thing on the page, or is it more like music, something that exists independently of its graphic representation with pen and ink (or pixel and screen). What is critical thinking and reading? I found myself thrilled by Brett’s reading, but frustrated that I couldn’t easily and in a single glance see how lines and stanzas fit together. I was, in some very real sense, at the mercy of the reader, no matter how much I loved his reading.

This raises necessary questions about the relationship between reader and listener. Could we tolerate a culture in which, like the ancient Greeks and Hebrews, reading is for the elite few while the rest of us listen or try to listen. At the mercy and good will of the literate elite—to say nothing of their abilities and deficiencies as oral interpreters of the works at hand.

More later

integrity that characterized

integrity that characterized  number XVII, republished as the following poem:

number XVII, republished as the following poem: temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance,

temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance,  of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.

of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.