I was glad to see this review of Tiffany Kriner’s Thought, Word, Seed: Reckonings from a Midwest Farm appear in Christian Scholars Review. As is probably evident, I loved Tiffany’s work here. I found my multiple reads of it over the past year (on my own and with students) to be not only aesthetically satisfying but spiritually moving and transformative. Also a lot of food for thought about how one goes about writing about books and reading. As my colleague John Fea is wont to say, a little taste.

I was glad to see this review of Tiffany Kriner’s Thought, Word, Seed: Reckonings from a Midwest Farm appear in Christian Scholars Review. As is probably evident, I loved Tiffany’s work here. I found my multiple reads of it over the past year (on my own and with students) to be not only aesthetically satisfying but spiritually moving and transformative. Also a lot of food for thought about how one goes about writing about books and reading. As my colleague John Fea is wont to say, a little taste.

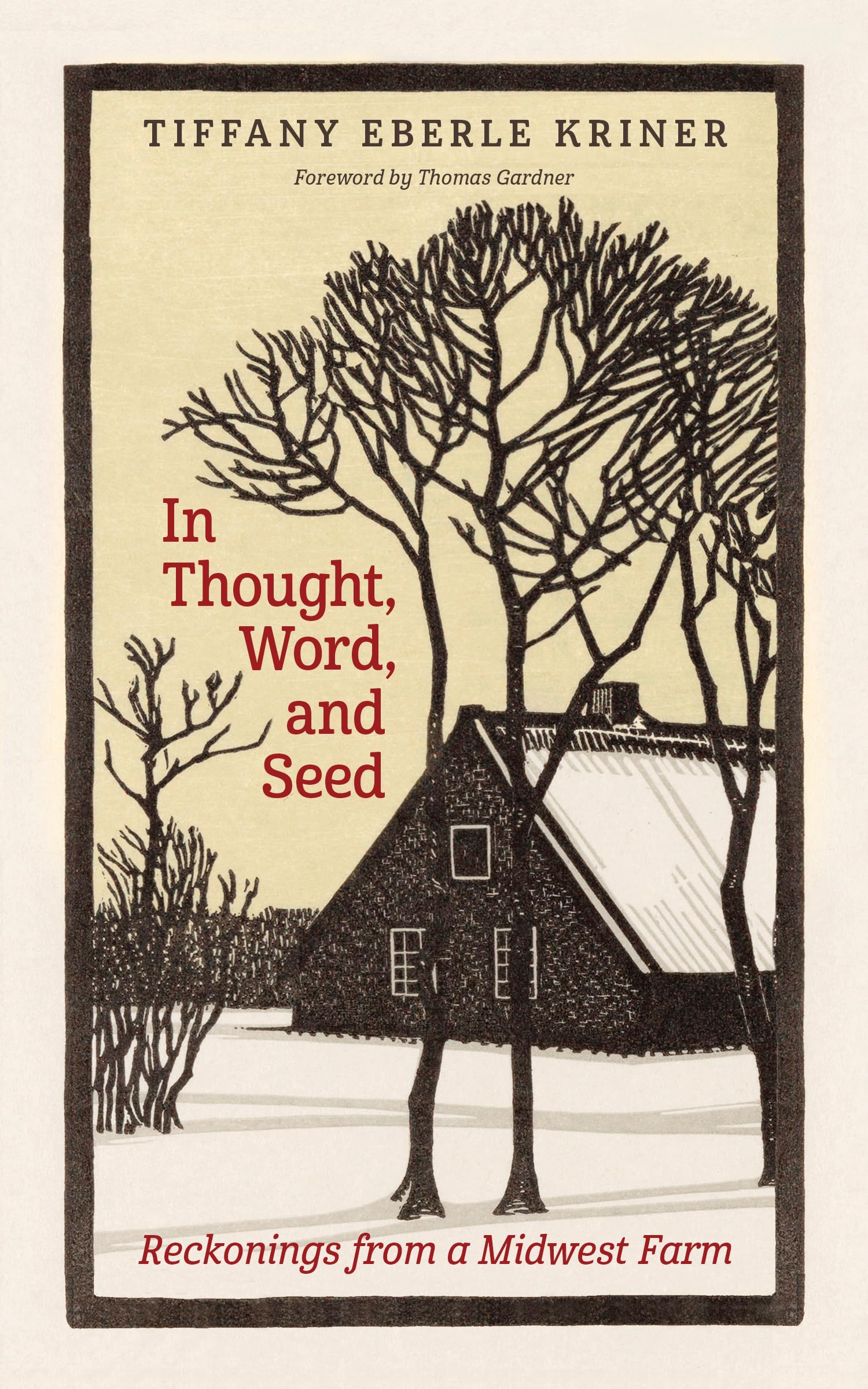

Tiffany Eberle Kriner teaches English at Wheaton College. She is also a mother, an organic farmer, a wife. She is a survivor of the pandemic, of cancer, of lesser deadly things like the tenure process. She is a writer. She is an anguished observer of the murder of George Floyd, a worrier that she may be a guilty bystander. She is a watcher of owls, a herder of sheep. She is, above all, a reader of books, of the Good Book and of the book of nature, of what we might call the book of the world. Charting how these selves and callings come together in one person on the Root and Sky Farm in rural Illinois during the pandemic and its aching aftermath is the subject of Kriner’s extraordinary memoir, In Thought, Word, and Seed: Reckonings from a Midwest Farm.

Thought, Word, and Seed is Kriner’s second book, following The Future of the Word: An Eschatology of Reading.2 It is, almost, hard to think of them coming from the same writer. The first is a provocative theoretical and theological interpretation of reading as an eschatological act, a means of making books live into the promise of the resurrection. It’s the kind of book academics reward with tenure and promotion and perhaps, if you are lucky, with footnotes and scholarly reviews.

However, in my own view, The Future of the Word is only prolegomenon to the achievement of In Thought, Word, and Seed. The second book is more memoir, more poetic. In a word, more “literary.” Yet, in some respects, Thought, Word, and Seed is a creative rereading of Future of the Word, making its ideas live in a different register, almost as if Kriner woke up one morning saying to herself, “Okay, if reading does the things I say it does, I need to write some other way, some new way, not that way.”

I hope you’ll enjoy Tiffany’s book as much as I did over the past year. As I say in the final line of the review, take up and read.