It’s a pleasure to pick up a novel and know from the first lines that it will be worth the read. We usually have to give more of ourselves over to novels than to other forms of writing–a problem in our frantic clickable age. With stuff that I remand to my Instapaper account, I can glance through the first paragraph and decide if I want to keep reading, and if I read three or four paragraphs and am not convinced it’s worth the time, there’s no point in agonizing about whether to keep on going. Same with a book of poetry: If I read the first three or four poems and there’s nothing there other than the authors reputation, I mostly put it aside–though I might admit that it is my failing and not the poets.

It’s a pleasure to pick up a novel and know from the first lines that it will be worth the read. We usually have to give more of ourselves over to novels than to other forms of writing–a problem in our frantic clickable age. With stuff that I remand to my Instapaper account, I can glance through the first paragraph and decide if I want to keep reading, and if I read three or four paragraphs and am not convinced it’s worth the time, there’s no point in agonizing about whether to keep on going. Same with a book of poetry: If I read the first three or four poems and there’s nothing there other than the authors reputation, I mostly put it aside–though I might admit that it is my failing and not the poets.

But novels are a different horse. A lot of novels require 50 pages and sometime more before we can get fully immersed in the writer’s imaginative world, feeling our way in to the nuances and recesses of possibility, caring enough about the characters or events or language or ideas (and preferably all four) to let the writer land us like netted fish. I think I’ve written before about the experience of reading yet one more chapter, still hoping and believing in the premise or the scenario or the author’s reputation. I’ve finished books that disappointed me, though my persistence was more like a teenaged boy fixed up on a date with with the best girl in school, pretending until the evening clicks to a close that he isn’t really bored to tears, things just haven’t gotten started yet.

But Madison Smartt Bell’s Doctor Sleep didn’t make me wait. I bought the book on reputation and topic. I loved Bell’s All Souls Rising, but got derailed by the follow-ups in his Haitian trilogy, never quite losing myself in the Caribbean madness that made the first book the deserved winner of an array of awards. Thus disappointed, I hadn’t really picked up Bell’s work since, though I vaguely felt I ought to. From the first sentences of the novel, his first, I was under the spell. The choice of words is purposeful since the book is about a hypnotherapist who, while helping others solve all manner of problems and difficulties through his particular gift at putting them under, cannot neither solve his own problems or put himself to sleep: He suffers from a crippling case of insomnia.

Like any good novel, the meanings are thickly layered. In some respects I found myself thinking of the Apostle Paul’s dictum that wretched man that he was, he knew what he should do, and he wanted to do it, but he could not do the very thing he knew to do, and, indeed, the very thing he did not want to do this was the very thing he did. The tale of all things human, the disjunction between knowledge and will, between thought and desire and act. The main character’s skills as a hypnotist are deeply related to his metaphysical wanderings amidst the mystics and heretics of the past, most particularly Giordano Bruno, burned at the stake because he claimed the church sought to promote good through force rather than through love. Ironically, the main character knows all this, knows in his head that love is the great mystic unity of which the mystics speak, and yet turns away from love in to abstraction, failing to love women because he cannot see them as human beings to whom he might be joined, seeing them instead as mystic abstractions through which he wants to escape the world.

In the end, accepting love means accepting death, which means accepting sleep–something that seems so natural to so many, but if you have suffered from insomnia as I do, you realize that surrendering to sleep is a strange act of grace, one that cannot be willed, but can only be received.

I think in some ways to there’s a lot of reflection in this book on the power of words and stories, their ability to put us under. So, perhaps inevitably, it is a book about writing and reading on some very deep level. Adrian, Doctor Sleep, takes people on a journey in to their unconscious through words, and his patients surrender to him willingly. Indeed, Adrian believes, with most hypnotists, that only those who want to be hypnotized actually can be. This is not so far from the notion of T.S. Eliot’s regarding the willing suspension of disbelief. I do not believe Adrian’s metaphysical mumbo-jumbo, but for the space of the novel I believe it utterly. We readers want to be caught. We want to lose ourselves at least for that space and that time, so that reading becomes a little like the gift of sleep, a waking dream.

Under the spell of writing we allow Bell to take us in to another world that is, surprisingly, like our own, one in which we see our own abstractedness, our own anxieties, our own petty crimes and misdemeanors, our own failures to love.

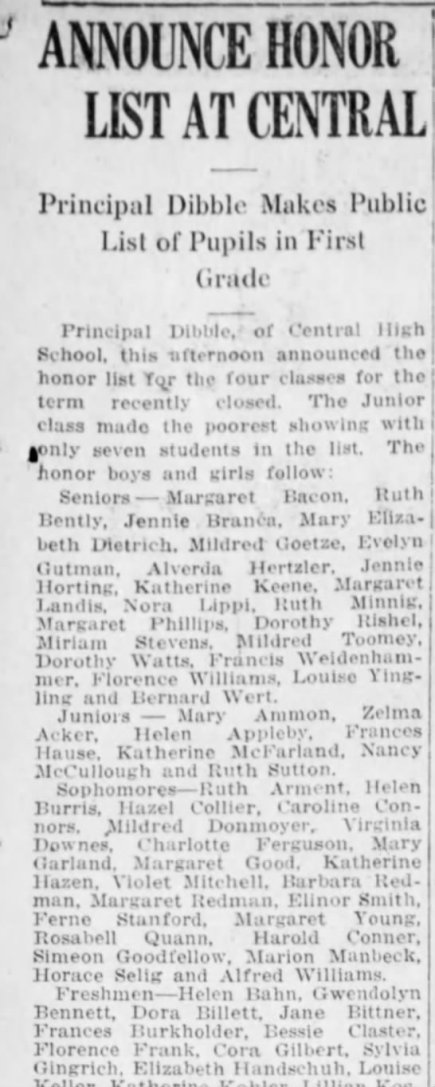

feel I know quite well. One thing that has continued to interest me is the ways in which the “Harlem” Renaissance extended and had connections to many places, including my home town of Harrisburg PA. I wrote briefly about Esther Popel Shaw’s connection to Harrisburg, and discovered, or was reminded (one of those things I think I knew, but never followed up on), that Gwendolyn Bennett, one of the most significant poets of the younger generation had a Harrisburg connection. According to this clip noted by Harrisburg Historian, Calobe Jackson, Jr., she made the honor roll in 1917.

feel I know quite well. One thing that has continued to interest me is the ways in which the “Harlem” Renaissance extended and had connections to many places, including my home town of Harrisburg PA. I wrote briefly about Esther Popel Shaw’s connection to Harrisburg, and discovered, or was reminded (one of those things I think I knew, but never followed up on), that Gwendolyn Bennett, one of the most significant poets of the younger generation had a Harrisburg connection. According to this clip noted by Harrisburg Historian, Calobe Jackson, Jr., she made the honor roll in 1917. At this point I haven’t been able to determine much more than these scant biological connections, but I am intrigued with the role that regions some distance from our cultural centers end up playing a role, major or minor, in the lives of our writers and in the larger movements that they create. I discovered a similar connection to Alice Dunbar Nelson that I’ll note in a later post.

At this point I haven’t been able to determine much more than these scant biological connections, but I am intrigued with the role that regions some distance from our cultural centers end up playing a role, major or minor, in the lives of our writers and in the larger movements that they create. I discovered a similar connection to Alice Dunbar Nelson that I’ll note in a later post.