One very big advantage of wireless networks. I can sit here and do this blog while I simultaneously watch American Idol. Yes, I am only partially ashamed to admit that I watch American Idol with my family every week. Listening to Simon disrespect singers for their “monumental lack of personality” is my great guilty pleasure.

Probably goes along with my general sense that we are too tenderfooted in declaring that some things are better than other things.

Thus, one way the net has it all over reading books. I mean I couldn’t sit here and read my new edition of War and Peace while listening to several people sing off key while displaying their lack of personality. Multi-tasking rules. (Who am I kidding; I don’t have a new edition of War and Peace or even an old one. I have no time.)

But today’s blog has nothing to do with that.

Ben Vershbow over at if:book posted a very interesting piece reviewing Hypertextopia, a free web space for writers wanting to explore the possibilities of hypertext for fiction. Says Vershbow:

The site is gorgeously done, applying a fresh coat of Web 2.0 paint to the creaky concepts of classical hypertext. I find myself strangely conflicted, though, as I browse through it. Design-wise, it is a triumph, and really gets my wheels spinning w/r/t the possibilities of online writing systems….

Lovely as it all is though, it doesn’t convince me that hypertext is any more viable a literary form now, on the Web, than it was back in the heyday of Eastgate and Storyspace. Outside its inner circle of devotees, hypertext has always been more interesting in concept than in practice. A necessary thought experiment on narrative’s deconstruction in a post-book future, but not the sort of thing you’d want to read for pleasure.

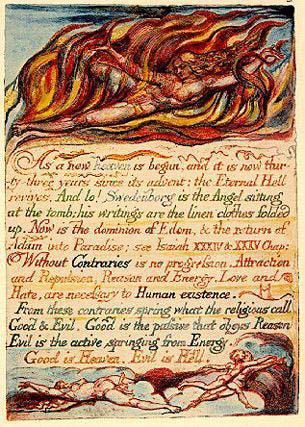

But those are the days I wish we could put the net back in the box and forget it ever happened. I get a bit of that feeling with literary hypertext — insofar as it reifies the theoretical notion of the death of the author, it is not necessarily doing the reader any favors.

Hypertext’s main offense is that it is boring, in the same way that Choose Your Own Adventure stories are fundamentally boring. I know that I’m meant to feel liberated by my increased agency as reader, but instead I feel burdened. What are offered as choices — possible pathways though the maze — soon start to weigh like chores. It feels like a gimmick, a cheap trick, like it doesn’t really matter which way you go (that the prose tends to be poor doesn’t help). There’s a reason hypertext never found an audience.

Hurrah! And Again. Hurrah. Vershbow has the courage to say that the king has no clothes.

That is, it’s not hip and cool to say, well, frankly, that this is all just a bit dull. But really, it is. It really, really is.

And hypertext fictions are boring in a way that the surfing the internet in general really isn’t. And the way old fashioned books are not. Almost as if the “planned” surprise or randomness or multiplicity of hypertext fictions are more controlling and in some fashion disrespectful of readers than traditional narratives ever were. And less surprising than the almost true randomness of the text or internet.

[Intertext I: Simon Cowell has just determined that the latest singer is “completely forgettable.” She is, she really, really is. Just like almost every hypertext fiction ever written.]

[Intertext II: I have definitely decided that Paula Abdul is irredeemably vapid. Not, I hope, like this post]

Vershbow is right to tie this to a peculiar failure of concept in postmodern views of reading and writing. I have to say that I love reading Roland Barthes. But his understanding of reading in “Death of an Author” completely misses the point of what is most pleasurable and imaginatively enlarging about the reading experience. That is, our self loss, our self-forgetfulness.

I don’t deny the general idea that reading is or can be a creative act. But Barthes tendency to turn every reader into a writer, every reading in to a writing, misses that the great glory of reading is transcendence of the self through loss, transcendence through the dissolution of the ego’s boundary, transcendence through the very submission of the imagination that Barthese hopes to forestall.

As if he were empowering readers by putting them in control. Perhaps he forgets that, as I learned on CSI, the passive partner in an S&M team is always the one who’s really in control, despite appearances.

Finally, equating freedom and creativity with control is….boring. Anyone who has written knows that the most exciting times aren’t those moments when you’re exercising authority over the text, but those when you aren’t. When the words say things you didn’t know or mean.

Reading as control is boring for the same reason hypertext fictions are boring. By giving the reader a job we’re confined by the randomness of our own choices, rather than freed and liberated from ourselves by the prisonhouse of someone else’s language.

Masochism, you say! So be it.

Submit yourselves to the discipline of the text…and be free.

Unless the grain of seed shall die. And so forth.

Fetishists of the text unite!

[Intertext III: Simon thought the last singer was “completely predictable,” but thought Brooke White was great. Paula Abdul says that Brooke White’s song was “really here.” What does that mean? What in the name of all that is good and true does that mean?]

Previews: I’ve gotten a lot of good responses to things lately that I just haven’t been able to get to. What I really hope to get to soon, but in case I don’t, just treat it like a movie that failed its test screening.

Sam Miller, one of my readers (that sounds pretentious, but I’ll say it anyway)has a new essay out at Conversational Quarterley that looks pretty good, but I need to read it more closely before I say more.

My good friend Julia Kasdorf has been up to her usual good stuff with reading and writing up at Penn State.

I’ve also managed to get the folks at MyAccess royally po’d. I think they’ve marshalled their hit squad of professional MyAccess users.

Also passed my two month anniversary as a blogger 3500+ page hits. And some of them are not even from the students I am paying to click through my pages (heh! heh!) Have got to talk about the compulsive addiction to write that is occasioned by anonymous readers.

But all that is for the future. After American Idol is over.

the nature of the comprehension we experience in reading versus listening. Second, while listening was taking place, there was more activation in the left hemisphere brain region

the nature of the comprehension we experience in reading versus listening. Second, while listening was taking place, there was more activation in the left hemisphere brain region  Emerson was a heretic who could say in all seriousness that poets are liberating gods, that we are part and parcel of God, and that he was a transcendatal eyeball (or something like that) creating the universe through his imagination. And we all thought Mitt Romney’s Mormonism might be just a little bit odd. What need the consolations of Christ when the advent of the world came through the exercise of the individual imagination, consort of the Oversoul?

Emerson was a heretic who could say in all seriousness that poets are liberating gods, that we are part and parcel of God, and that he was a transcendatal eyeball (or something like that) creating the universe through his imagination. And we all thought Mitt Romney’s Mormonism might be just a little bit odd. What need the consolations of Christ when the advent of the world came through the exercise of the individual imagination, consort of the Oversoul? temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance,

temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance,  of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.

of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.