I’ve finally finished reading Pierre Bayard’s How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read, and thought I’d talk about it, perhaps for the next couple of days as I think through it.

The first thing to say is that every element of the sentence I just wrote is nonsensical in Bayard’s understanding of reading.

First, one can never really claim to having finished reading a book since, in fact, we don’t actually read books in the first place, though we sometimes fool ourselves into believing that we do. Bayard goes to great lengths to point out that every act of reading is foremost and always an act of forgetting; even as we turn the page—indeed, even as we leave one sentence behind for another—we engage in a gradual process of forgetting most of the details of what we have read. What we retain is not so much the book as an image of the book that corresponds to our general sense of books as such, of the vast panoply of possible and actual books in their real and imagined relations. Every book we have read is, in some fashion, an act and creation of the imagination. We, therefore do not really finish books so much as we use books to engage with this great library of the imagination that lurks within.

Second, and following on the first thesis, I could not really claim to have read Pierre Bayard’s book since in Bayard’s conception we do not really read things that are exterior to ourselves, and we fall in to desperate traps when we let books lead us into thinking that we do. He is much taken in the beginning and end of his book by Oscar Wilde’s great essays “To read, or not to read” and the seminal “The Critic as Artist”–essays that Bayard seems, against the implications of his own theory, to have read closely and been affected by deeply. For Wilde, of course, criticism is not so much a secondary act of reading a prior text as it is an independent creation more on the order of autobiography. (Side note: Bayard would be much intrigued by my use of the phrase “of course” in the sentence just finished) Thus, in spinning out these musings on Bayard, I am in fact engaging more properly and obviously in an extended act of autobiography than in any actual reading of Bayard in and of himself. To some degree this is Roland Barthes lite, especially in his essay “The Death of the Author” wherein Barthes champions reading not as an engagement with the prior authority of an author but an act of creation that celebrates the creative capacities of readers.

Third, and following on this second point, I could not really be talking about Bayard’s book, though, of course, I may fool myself into believing that I am Instead, we are always only talking about books we haven’t read. Much in the spirit of Stanley Fish’s discussion of free speech—There’s no such thing as free speech, and it’s a good thing too—we hear Bayard saying. There’s no such thing as reading books, and it’s a good thing too.

Finally, if all this is true, I cannot really be thinking through Bayard’s book since I will mostly, in fact, be thinking through the activity of my own imagination in the first place.

[A pic of Pierre Bayard looking like an insouciant American teenager. No, wait, it’s a photo  of an American teenager attempting to look like an insouciant French intellectual. No, wait, Bayard attempting to reflect the idealized image American adolescents have of French intellectuals. No, wait….]

of an American teenager attempting to look like an insouciant French intellectual. No, wait, Bayard attempting to reflect the idealized image American adolescents have of French intellectuals. No, wait….]

There’s a lot to say about Bayard’s book—or rather about the play of my own imagination—and I hope to get to a few of them over the next day or two. But the first thing I want to note is that though this book has been a splash in the United States, it is a thoroughly French book. In saying this, I am exercising one of Bayard’s dicta that understanding the place of a book within the universe of books is more important than reading it. Be that as it may, it seems to me that this book is more important for the French than it is for Americans, but if this is so, how should we account for its popularity, or at least its press, in the United States.

First, what do I mean by the statement that it is a thoroughly French book? Witness Bayard speaking somewhat self-indulgently of his own courageousness in facing down constraints against admitting the real character of our reading.

“The first of these constraints might be called the obligation to read. We still live in a society, on the decline though it may be, where reading remains the object of a kind of worship. This worship applies particularly to a number of canonical texts—the list varies according to the circles you move in—which it is practically forbidden not to have read if you want to be taken seriously.

“The second constraint, similar to the first but nonetheless distinct, might be called the obligation to read thoroughly. If it’s frowned upon not to read, it’s almost as bad to read quickly or to skim, and especially to say so. For example, it’s virtually unthinkable for literary intellectuals to acknowledge that they have flipped through Proust’s work without having read it in its entirety—though this is certainly the case for most of them.

“The third constraint concerns the way we discuss books. There is a tacit understanding in our culture that one must read a book in order to talk about it with any precision. In my experience, however, it’s totally possible to carry on an engaging conversation about a book you haven’t read—including, and perhaps especially, with someone else who hasn’t read it either. ” (xiv-xv)

It’s possible, of course, to imagine certain narrow circles in the United States where people still feel the obligation to have read, and especially to have read certain texts. However, this surely reflects the educated classes of France far more than the U.S., places where literature still really bears a distinct form of cultural capital. But can that be said of any but the narrowest intellectual circles in the United States? With no apparent compunction, Steve Jobs dismissed the idea of developing an e-book reader, simply on the basis that it is a bad business model. No one reads in the United States anymore, so why bother. This hardly sounds like a man worried about the fact that reading is still worshipped in his culture of reference.

Even with academic circles in the United States, the fragmentation of cultural knowledges means that academics simply accept the fact that they will read a great deal that no one else around them will have read. And the increasingly arcane specialization of literary studies means that even those texts we abstractly share as “Must Reads”–say something from Shakespeare–are hardly shared as forms of cultural capital. My having read Hamlet gets me no points with my colleague who is an expert in Shakespeare—so what, he says, have you read the latest biography theorizing the importance of Shakespeare’s lesbian grandmother? My having read or not read Hamlet gives me no cultural capital with my fellow specialists in African American literature. Haven’t read Hamlet? Good riddance. Americans live in a country where presidents glory in their non-reading and have no shame in their literary ignorance. Indeed, such ignorance can be a badge of honor. The crisis of guilt Bayard pretends to address could only be a foreign crisis of little interest to the actual scene of reading in the United States.

This having been disposed of, the inconsequence of Bayard’s second and third constraints on the American scene must be quite clear. In the United States, we are generally pleased if people read at all, so we could hardly care if they read thoroughly—except for the short and inconsequential spaces of time that students spend within English classes. (Even here, I find most English profs are simply relieved if their students have read the texts at all, much less whether they have read them thoroughly) Finally, of course, we don’t generally talk about books anyway except in very narrow circles that have cult-like characteristics, with the fortunate bonus that they are easily escaped. If I get tired of my book-loving pals in the United States, I can go….well….almost anywhere to find people who think that booklovers are a bit queer, in both the old and new senses of the word. The guilt that Bayard hopes to rid us of is, in the United States, hard to find.

Why then his book’s splash in all the reviews? I think in part this is because the reviews are the last places in America where people seem to care whether Americans read or not, and where what you have read has some consequence. So Bayard is speaking to that increasingly narrow segment of the American population that bothers to read book reviews of academic books and thinks they are worth thinking about. Secondly, however, the book comes just at that moment when we have had an uptick in media concern with the status of reading generally. While Bayard is attempting to unmask the hidden practices of reading in France where reading continues to carry the force of cultural capital, in the United States he speaks not to our guilt but to our self-affirmation. Oh, we’re not really reading books at all even when we are reading them. Good thing I wasn’t pretending in the first place.

Whereas Bayard’s book functions to unmask an ideology of reading in France, it mostly reaffirms the practice of most 18 year olds in general education literature courses. Haven’t read the book. No problem. Read Spark Notes and bullshit your way through. Bullshitting as a valuable adolescent form of creative self-display.

More later, but first a confession. I haven’t really finished Bayard’s book. I have ten pages to go. I’m wondering why I didn’t follow his advice in the first place.

the nature of the comprehension we experience in reading versus listening. Second, while listening was taking place, there was more activation in the left hemisphere brain region

the nature of the comprehension we experience in reading versus listening. Second, while listening was taking place, there was more activation in the left hemisphere brain region

As my colleague, Matt Roth, suggests it’s hard to know which is worse, that they made the bed in the first place, or that they didn’t know about

As my colleague, Matt Roth, suggests it’s hard to know which is worse, that they made the bed in the first place, or that they didn’t know about  temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance,

temple reader and the town crier are the original of audiobooks and podcasts. In ancient Palestine, for instance,  of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things.

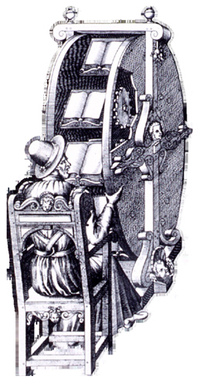

of them at the same time. This is not exactly the same thing as multi-tasking that Scott abhors in his post, and it’s not exactly internet hypertexting, but it is clearly not the singular absorption in a text that we’ve come to associate with the word “reading.” “Reading” is not just the all-encompassing absorption that I’ve come to treasure and long for in great novels and poems, or even in great and well-written arguments. Indeed, I judge books by whether they can provide this kind of experience. Nevertheless, “Reading” is many things. taken by the classic image of the hunched body at the desk, but also that it was obviously a middle-aged man, somewhat monkish. Finally, that you couldn’t see the face—which seemed to me to be something about reading and something about what I wanted the blog to be. Reading is a kind of facelessness, a kind of disappearance of the self that is itself enriching and expansive. This is why I think all the focus on reading as creativity and self-assertion among so many poststructuralists—people like Roland Barthes who want to turn reading in to an alternative form of writing—is missing something that’s relatively essential and important. The disappearance of the self in reading is precisely what we desire. The loss of self is goal, not dread outcome of the process of reading.

taken by the classic image of the hunched body at the desk, but also that it was obviously a middle-aged man, somewhat monkish. Finally, that you couldn’t see the face—which seemed to me to be something about reading and something about what I wanted the blog to be. Reading is a kind of facelessness, a kind of disappearance of the self that is itself enriching and expansive. This is why I think all the focus on reading as creativity and self-assertion among so many poststructuralists—people like Roland Barthes who want to turn reading in to an alternative form of writing—is missing something that’s relatively essential and important. The disappearance of the self in reading is precisely what we desire. The loss of self is goal, not dread outcome of the process of reading.

of an American teenager attempting to look like an insouciant French intellectual. No, wait, Bayard attempting to reflect the idealized image American adolescents have of French intellectuals. No, wait….]

of an American teenager attempting to look like an insouciant French intellectual. No, wait, Bayard attempting to reflect the idealized image American adolescents have of French intellectuals. No, wait….]